Today, I will be thinking a lot about my dad and his boyhood friends.

I’ll think about how, on the morning of February 7, 1958, my father had convinced himself that the awful news he had heard when he arrived home from school the previous afternoon, had been nothing but a bad dream.

My nan had entered his bedroom that morning to wake him for the day. Still in that half-eyed, sleep-drunk state you sometimes find yourself in after slumber, he told her all about his dream. There had been a plane crash, he recounted.

The mighty Manchester United side of 1957/58, the one he and his friends would get the bus from Eccles to Old Trafford to watch every other weekend, had been on the aircraft. Many were injured; some had even died.

Taking his hand in hers, she interrupted his tale. “It’s true, love,” she said softly.

By his own admission, my dad’s memory isn’t as sharp as it once was. And yet he remembers this moment – which he still describes as one of the worst in his life – with vivid detail.

In fact, he remembers lots of things about the days and weeks that followed the Munich Air Disaster, which claimed the lives of some of his childhood heroes.

He remembers how, later that same morning, he and several other boys of a similar age, had started sobbing uncontrollably in the school hall, to the point where the morning assembly had almost been cancelled.

He remembers taking in the first grainy bits of footage and black and white photos of the twisted metal that made up the aircraft’s wreckage, lying in the snow of the runway at Munich‑Riem airport.

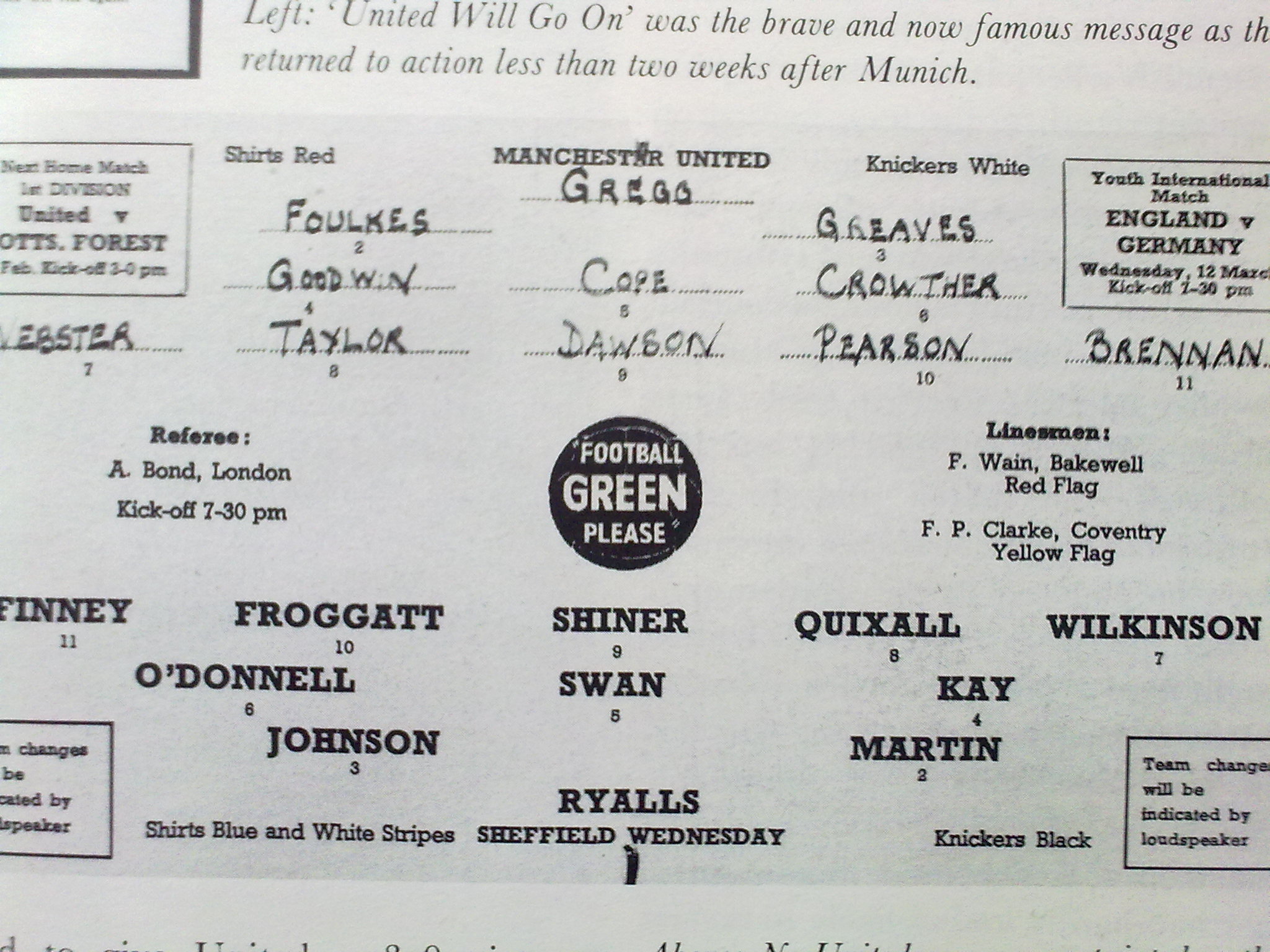

He remembers arguing with his parents about not being able to go to the FA Cup game against Sheffield Wednesday only two weeks after the crash, where a patched-up United XI were carried by an emotional crowd to a 3-0 victory.

He remembers how, when he attended the league match against Nottingham Forest the following weekend, he and a friend had been crushed to an inch of their lives against the Old Trafford railings, by the sheer volume of grieving fans flooding on to the terraces to see their stricken team.

He remembers clinging to the hope that his idol, Duncan Edwards, who had survived the initial crash, would pull through.

He remembers hearing the news on February 21, that he had not.

My dad, like so many others of his age, had fallen in love with football because of that United side. It was a team that many sensed were on the cusp of greatness: good enough to dominate European football for a decade to come.

Alas, fate intervened in the very cruelest way to ensure they would not.

A decade later, my father drove his red (obviously) Mini Cooper down to Wembley to see Sir Matt Busby and his refashioned United side lift the club’s – and English football’s – very first European Cup.

That night, as with every anniversary for the last 60 years, those who perished as a result of the third attempt at takeoff on a wintry Bavarian afternoon, were clear in his thoughts. Joy was tinged with a special poignance.

As much as he would love to be there, my dad won’t be attending the memorial service at Manchester United on Tuesday. A newly-replaced knee has seen to that.

This, along with the heart attack he suffered last year, has forced him to seriously consider whether he will be renewing his season ticket in the summer.

If he doesn’t, he will be just another fan old enough to recall the famous Busby Babes, who is lost to matchday at Old Trafford. Another link to the past to fall away.

He’s in his seventies now – over half a century older than the great Duncan Edwards when he passed – and very much aware that he isn’t getting any younger.

Life goes on, he says, whether you like it or not. And while the Munich Air Disaster may have been a very long time ago, it continues to remind us of just how cruel it can be. There’s no special cases, no immunity from cruel fate.

Sometimes even your heroes can die.

RIP The Flowers of Manchester.