Apart from the organised doping, the abandonment of a whistleblower, the fabrication of a robbery, the allegations of corruption in boxing, the arrest and detention of a member of the IOC, the unnecessary spending in a country whose vital services could do with the money, the scandal of the Paralympics and the cloud that has hung over a number of medal winners, the Olympics have been glorious.

But they have been glorious, despite all that. At their best, the Games can transcend this murkiness. Every four years we learn about sportspeople most of knew nothing about. The joy people took from the achievements of the likes of the Brownlee brothers and the champion cyclists was genuine and moving.

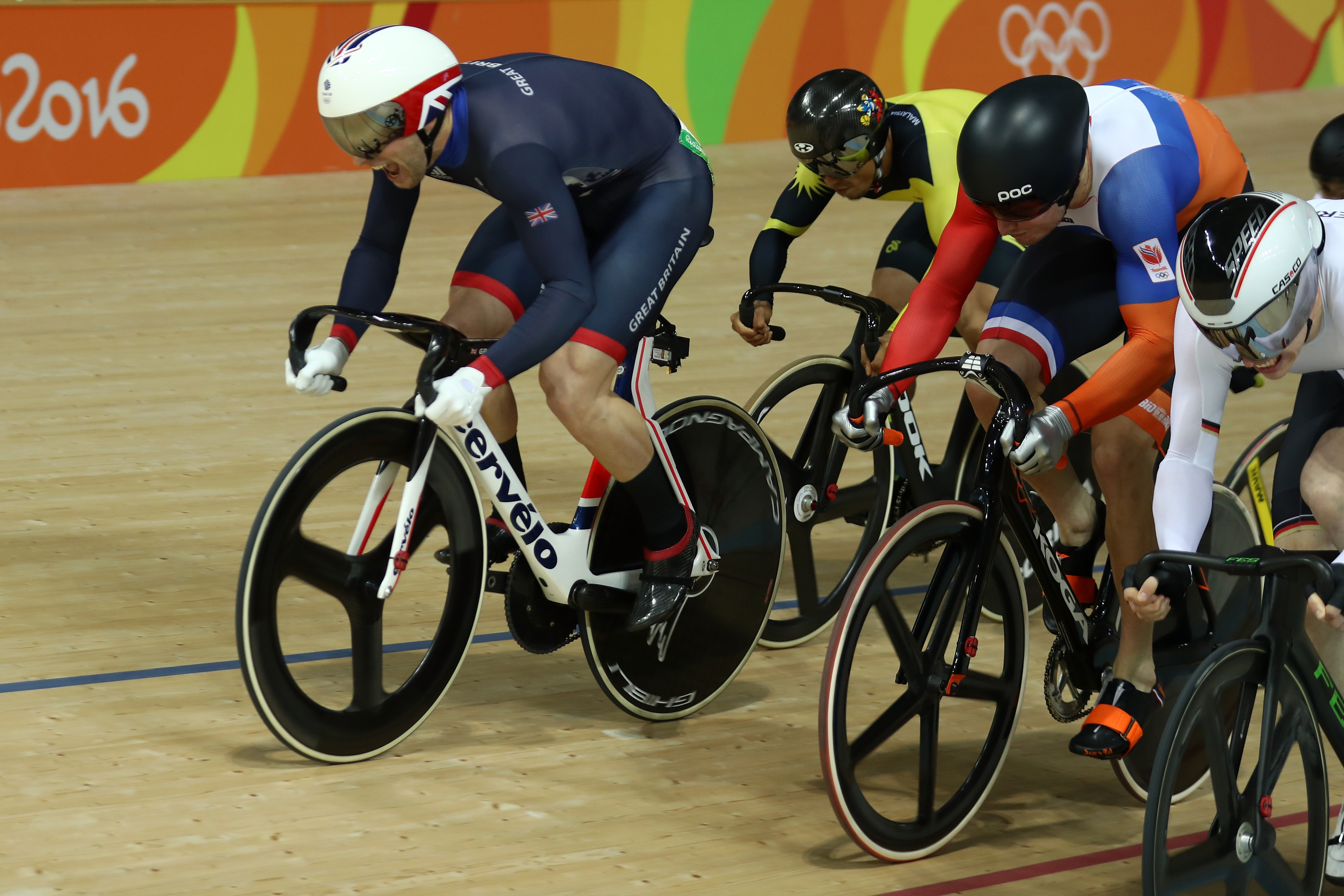

In Britain, the record medal haul has made the country feel good about itself. Some have said it is an antidote to Brexit, although this has yet to be reflected in, for example, the currency market which continues to take its lead from one of the most egregiously self-destructive acts in modern European history rather than, say, what happened in the Keirin.

All that celebrating has led some to wonder why it can’t be like this all the time, why can’t they feel this good and enjoy sport, perhaps as it is supposed to be enjoyed, more often?

Of course, some will wonder rightly about all this too, especially in events that due to their history could be preceded by a man waving a red flag.

On Tuesday, Team GB arrived home. They have been rightly hailed for their tremendous achievements and the incredible dedication they have shown to their sport.

As people reflect on the Olympics and the joy it brings, they seem to feel a great dissatisfaction with their everyday lives, but instead of putting it quite like this, they turn on football, the sport which is a central part of their everyday lives.

This is part of the cycle now. When England won the Rugby World Cup in 2003, some wondered why football could not learn from the heroics of the rugby team. In 2012, the Olympics in London were such an all-consuming celebration that it felt like a brutal reintroduction to the real world when the football season began.

It's happened again… https://t.co/RRPVnCrqDe

— FootballJOE (@FootballJOE) August 22, 2016

But there is a reason for this. Football brings joy too, but it is not primarily about that. It is not a pastime or a hobby for many, it a central facet of their existence.

“No player, manager, director or fan who understands football, either through his intellect or his nerve-ends, ever repeats that piece of nonsense – ‘after all, it’s only a game’,” Arthur Hopcraft wrote in 1968. “It has not been only a game for 80 years: not since the working classes saw in it an escape route out of drudgery and claimed it as their own.”

Football mattered, Hopcraft believed, because people could not be fooled, because they owned the art form in a way they couldn’t own any other art form.

This is why football is the world’s game and, more than ever, is seen as an escape route to someplace else, even if the audience has changed dramatically.

As we watch the diving and wait for the big splash or the small splash, while wondering if a high tariff is needed to get our man back in the competition and indeed what a high tariff is, we are taking a break from things, enjoying ourselves and getting carried away in a world we know nothing about.

The Olympics is the cousin you meet at a wedding and wonder why you don’t spend more time with them. You’re out there having a great time, dancing as if nobody is watching and wishing the weekend would never end. But, of course it, does. The sun comes up and life goes back to normal until you see them four years later at another wedding and find yourself promising that this time you really will stay in touch.

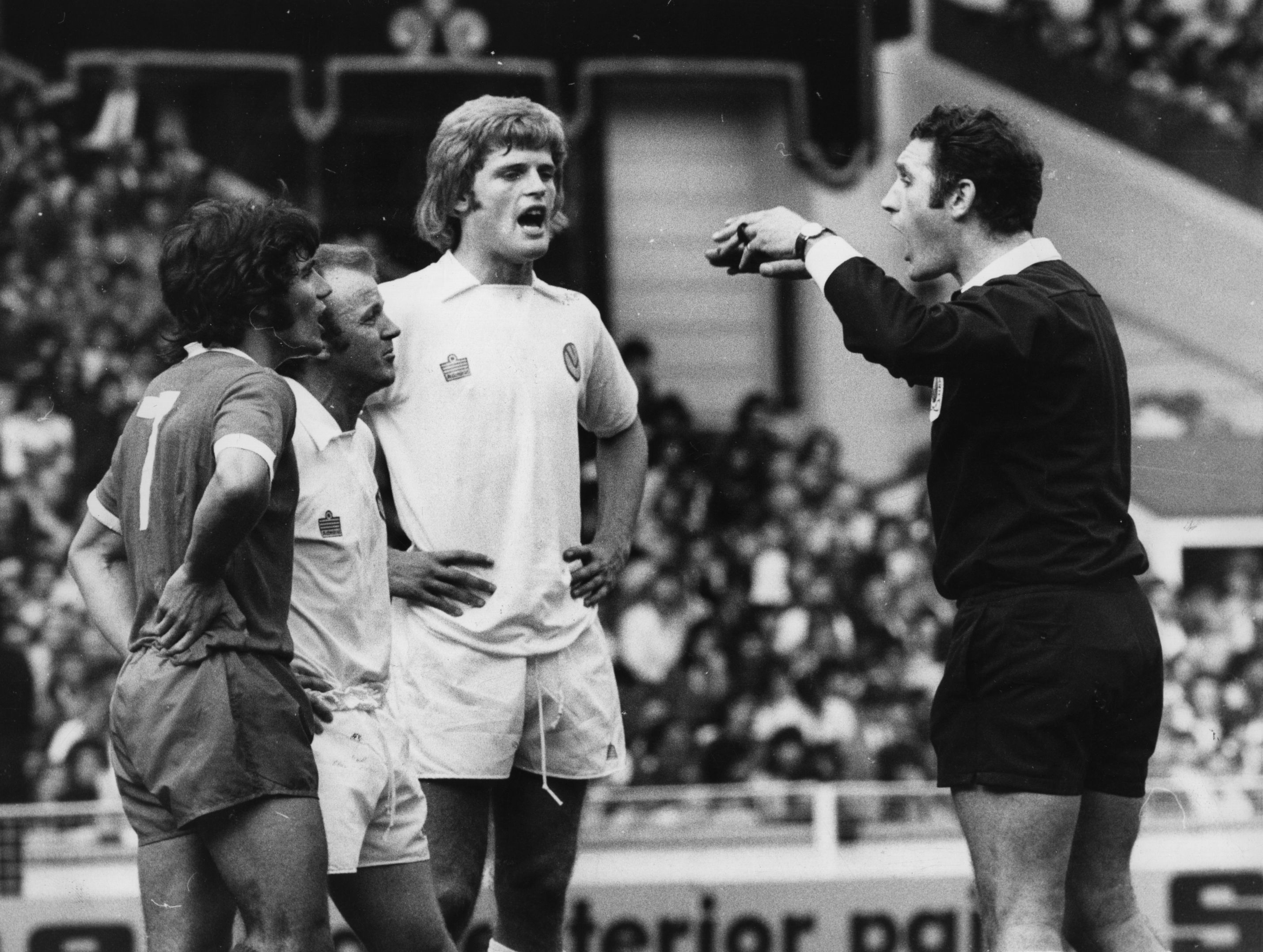

Football, on the other hand, is Monday morning. It is, of course, Saturday night too. And every other day of the week as well. It is who we are, it is entwined in every aspect of our lives which means, like many other aspects of our lives, there are times when all we feel is self-loathing.

The tribalism which many understandably find distasteful is a direct consequence of this importance. Liverpool v Manchester United has a different atmosphere to the laser radial, but that is because, quite simply, it matters more to more people. Maybe it shouldn’t, but then football would have to be a different game with different roots.

It is not just the Premier League even though that is seen as the villain. More than 40,000 people watched just three games in League One at the weekend with Bolton, Bradford and Millwall at home. These attendances tell of the deep and profound meaning football has for many.

The money which has entered the game as a direct consequence of its popularity is now seen by some as something grotesque. Although perhaps it is that people feel it is grotesque that it has fallen into the wrong hands, into the hands of working-class kids who lack the refinement and taste to know what to do with it, who use it instead as an escape from the drudgery which otherwise might have been their lives.

If people really had a problem with football’s popularity they could simply make it less popular. They could watch badminton or gymnastics instead, but they choose in massive numbers to watch football which is why television companies consider it worth their while to spend several billion pounds on the TV rights.

This money has changed the lives of those who play it at the highest level. But what has transformed their lives in the first place is not the money, it’s the dedication and talent in a ruthlessly competitive field. They succeed in a world where there is no hiding place and a world where the relentless criticism from those who believe their wealth essentially means they now belong to the spectators.

Some may have watched the Olympics and agreed with those who wanted footballers to be more like the Olympians, but we would probably all have to be more like the Olympians in that case. That can’t happen. The Olympics are a glorious escape. Football provides a route out too, but we can’t escape it, because it is part of who we are, not who we want to be.