Anorexia didn’t just starve me of food.

It starved me of my family.

It starved me of my friends.

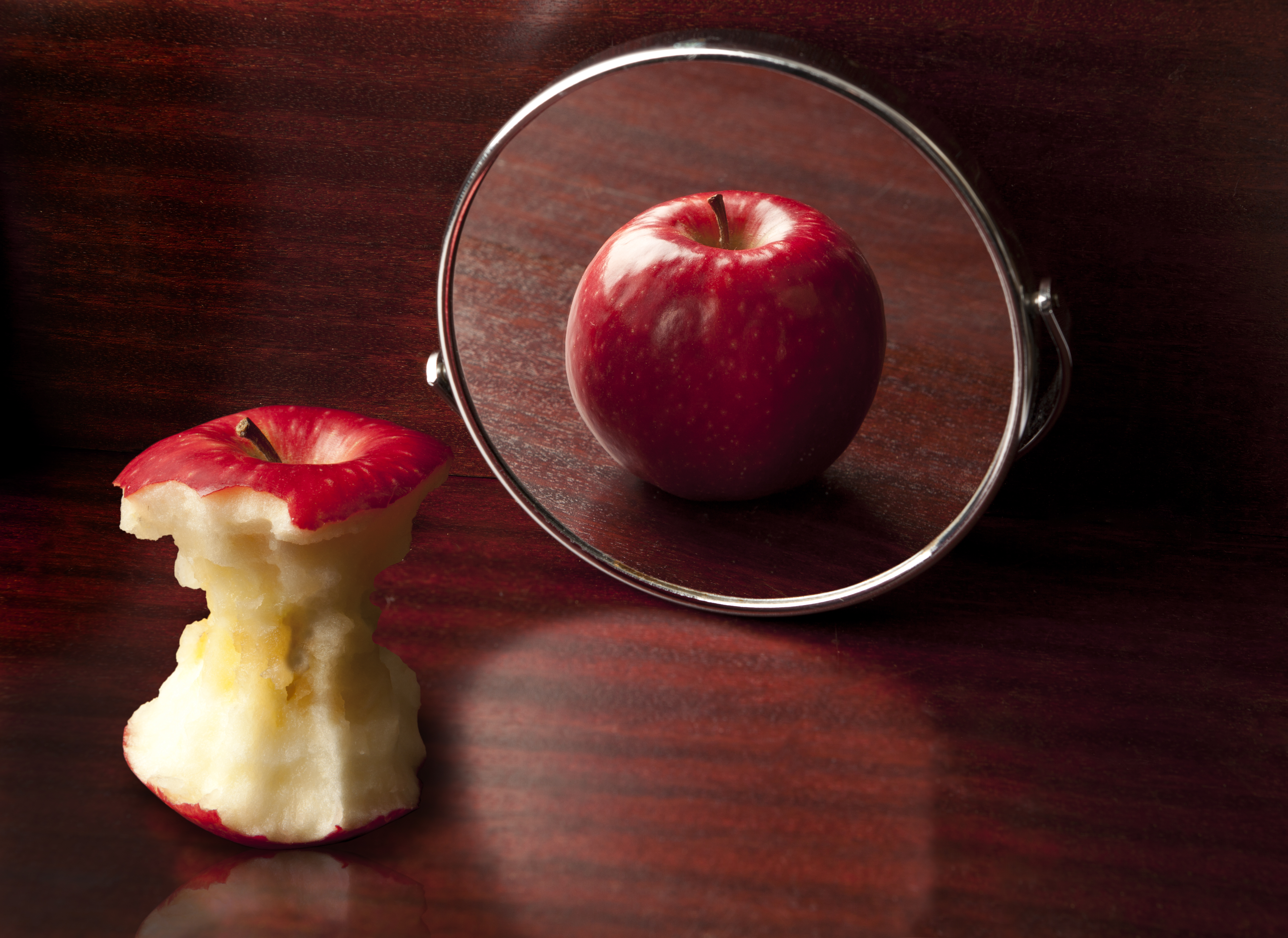

It denied me any chance of ever feeling comfortable in my own skin.

Ask yourself, “what do I know about eating disorders?”

Your mind may likely rush to the clichéd scenario of supermodels forcing two fingers down their throat in the backstage bathrooms of fashion shows; an example which I too would have thought of before anorexia hit me.

Eating disorders have never been given the level of exposure or viewed in the same light as some other mental health issues, yet studies have proven that the mortality rate among anorexia sufferers ranks among the highest in comparison to the rates of death in sufferers of other psychiatric illnesses.

I have anorexia. I have bulimia. And I have depression.

I say “have” because I don’t believe I will truly get over them, but I am doing a hell of a lot better now than I once was.

Anorexia kick-started my experience with mental illness.

An experience with a school bully roaring “you fat bitch” led to my decision to do anything and everything possible to force myself to lose weight.

‘Anything and everything’ involved getting up earlier than my parents, toasting bread and tossing everything but the crust and crumbs into the bin so that it appeared that I’d had a decent breakfast.

‘Anything and everything’ involved punching myself in the stomach, willing my body to purge itself of any minuscule meals I’d actually eaten, before patiently waiting until the blood and bile arrived so that I could unlock the bathroom door, satisfied that every last morsel had been removed.

At 12 years old, I weighed 12 stoneI developed depression.

It became a sickening cycle of one mental illness perpetuating the other, as I’d feel fat, I’d feel shit, I’d vomit, I’d binge-eat to fill whatever fucked up void I felt within me, before feeling fatter than I’d felt before I’d purged myself.

That, along with the emotion of having ruined the great “get yourself thin” plan, cultivated a sense of self-loathing that showed itself in several instances of self-harm and two suicide attempts.

There was definitely a lot more to eating disorders than that supermodel cliché.

Anorexia enlightened me to the fact that eating disorders are by no means exclusive to young twenty-something girls like myself, contrary to what a surprising number of people may genuinely believe.

In particular, my time as an inpatient pulled back the curtain on one of the greatest misconceptions of eating disorders; my eyes were opened to the fact that they are by no means a gender-specific disease.

To put it very bluntly, eating disorders don’t fucking care about your genitals. They destroy all lives equally.

Matt (name changed for privacy reasons) was a boy from Dublin who was probably a year older than me. He would always have these burn marks over the veins on his wrist and he was the only male inpatient being treated for an eating disorder on my ward. We became quite friendly in the common room in the afternoons and one day he explained to me how difficult it was being a young guy with anorexia.

I tried to assure him that I knew what he was going through when, in truth, I felt that he was enduring a significantly more testing experience with the same disease.

“When my parents were told by the doctors I had anorexia, their reaction probably made my stomach sicker than the starvation ever could,” he told me. “They thought it was a female disease ‘that only girls could get’.”

In that instant, I realised that my experience was very different to Matt’s.

We shared the common symptom of the emaciated frame which typically accompanies the self-restricting habits of an anorexic, but having his illness dismissed as something that was impossible for a young boy to go through left him with no outlet.

At least people listened to me.

Matt’s illness was not being taken remotely seriously by the people who should have been showing the most care.

His parents had brushed off the disorder and that must have made an already steep, uphill struggle of a young male sufferer all the more taxing.

It’s a side to eating disorders that is seldom discussed in the media and that in itself makes it so much harder for men to speak up when they’re struggling, maybe due to the fear of being perceived as less masculine?

In reality though, masculinity and femininity have absolutely no bearing on the issue.

The disparity between female and male sufferers of eating disorders in the United Kingdom is not nearly as vast as you might imagine.

An NHS study found that estimated 1.6 million people in Britain are suffering from some form of an eating disorder, and as many as 25% of those may be males.

But the lack of coverage and public awareness of the male side to the story would lead you to believe that the ratio is closer to 99:1 and this simply isn’t the case.

Dialogue is crucial for sufferers of not only eating disorders but all mental illnesses. Talk and, if you’re a parent, listen.

A huge chunk of my life has been taken up with trying to overcome this, and speaking out helps.

Mental Health Awareness Week takes place from Monday May 8 – Sunday 14.

For support or more information on Eating Disorders you can contact:

B-eat: 0808 801 0677

The Laurence Trust: 07510 371 335

National Centre for Eating Disorders: 00845 838 2040

MenGetEatingDisordersToo.Co.Uk

Priory Group: 0800 086 1997