Sport and music. When you’re young, there often is nothing else. These are the things you lose yourself in. These are your safe places.

Parents dropped their kids off at the Ariana Grande concert in Manchester on Monday night with all the quotidian anxiety and worry that are part of letting your children go anywhere.

It was a concert just like any concert which, conversely, allowed children to relish their freedom. They might have felt the release from the rules and regulations, and the everyday concerns of a teenager, which of course, feel like the greatest concerns in the world.

In the Manchester Arena, they were free. Meanwhile their mothers and fathers waited, maybe mentally noting the clock ticking down until it was time to collect them. Some, perhaps, with that low thrum which is the mood music for parents who always worry, who are always concerned whenever they let their children go.

And, as these children left the concert, as they returned to the parents who were waiting outside, to the parents they may have secretly missed while they were being young and free, they were caught up in terror and murder.

People were murdered, not because they were teenagers or music fans or parents, but because the foyer of the Manchester Arena provided an opportunity for the deranged to commit an act of savage inhumanity.

Of course, it could have been a shopping centre, a train or a bus that provided this opportunity to kill and to create an atmosphere of fear and hatred. It could have been anywhere where people are gathered together, but it was at the end of a pop concert in Manchester. And it is Manchester that provides a tiny bit of solace at this time of overwhelming sadness.

When you grow up obsessed with football and music in Ireland, it is almost inevitable that certain British cities take a hold of you. In the 1980s, you were tone deaf if Manchester wasn’t one of them.

It was the place that produced Johnny Marr (born John Maher) and the rest of Smiths, Joy Division and the Stone Roses. It was the city of the Hacienda and Tony Wilson. It was the town that had provided a stage for Liam Whelan and mourned him and his team-mates in 1958, consequently becoming a club with a spiritual connection to Ireland. Manchester was a place where you could lose yourself in romanticism, but it had a real connection too which was more than just romantic.

“Manchester has been home to the Irish and so many nationalities for centuries,” President Higgins said in his statement on Tuesday, “and at this terrible time I want to send the people of this great and welcoming city not only our sympathy but our solidarity.”

That was the truth of these great cities. London, Glasgow, Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester provided the Irish with opportunity, even if so many were lost as well in the pubs of Salford or East Kilbride or Shepherd’s Bush.

But there has always been a feeling of solidarity, a sense of recognition and an acknowledgment of that welcome, especially from the great northern cities of Manchester and Liverpool which were shaped by Irish emigrants.

There is, as Enda Kenny put it on Tuesday, “an Irish thread to the life and soul of Manchester.” But there is no need to romanticise the past to feel a pull towards the city at a time like this.

There is a thread for many across the world to the life and soul of Manchester. Since the industrial revolution drove people from the fields to the cities, to the “dark Satanic mills” that provided employment in the cotton industry, there has been a connection between the great city, those who made it their home and those they left behind.

There is a thread from the industrial revolution to the music and football that captured the imagination 150 years later to the defiance and unity that the city showed on Tuesday as it came to terms with the terrorist attack.

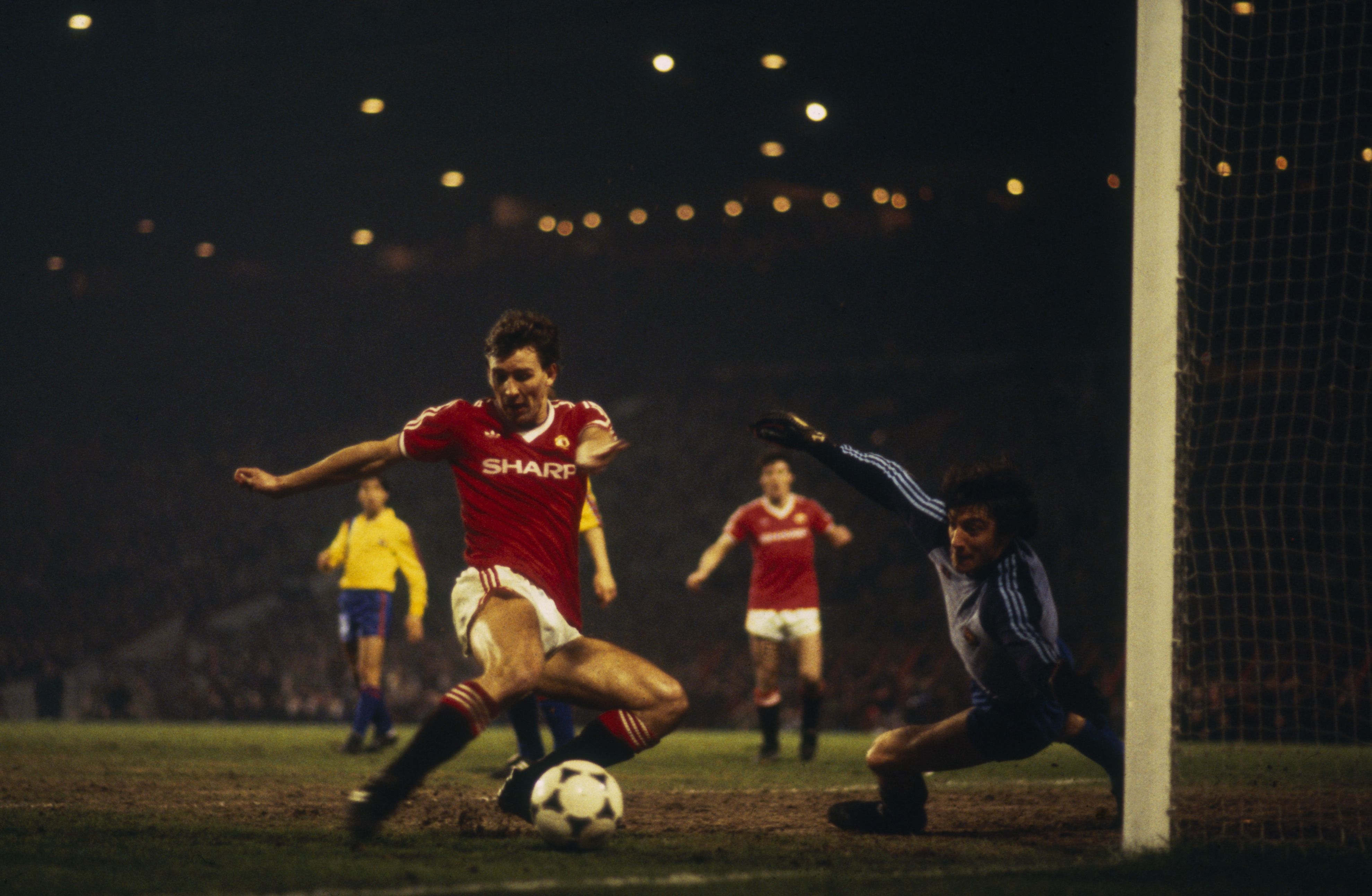

In Stockholm on Wednesday, Manchester United, a club that draws its support from around the world, will be representing a city where people are bewildered and lost.

On Tuesday, there was a reflex response which said that sport ‘pales into insignificance’ when placed up against this horror. Yet its significance and the significance of music remain potent.

It still matters. It doesn’t turn pale, it becomes vibrant. Sport, like music, remains a place where we go to belong, to experience that sense of freedom and wonder. And when that feels impossible, maybe all it does is allow us to forget momentarily life’s horror.

Nothing Manchester United do has any meaning when placed against the terror of Monday night. A Europa League victory has limited worth as an act of defiance or consolation when children have been murdered.

But it will be a reminder of the qualities of the city and its people.

“Mancunians were a special breed, circumstances had determined that,” Eamon Dunphy wrote in A Strange Kind of Glory, his outstanding biography of Matt Busby which was also an unsentimental ode to Manchester.

“They were generous. Generous had been a currency in each community, but each community was separate – until football drew the city together. Watching football… the docker stood beside the mill-worker. For the son of Irish immigrants and Scots… for all who were unsure of what they were, who had broken free of their roots in order to survive and now were desperate to belong, football offered a unique opportunity to discover and declare a sense of pride.”

In truth, it was not just football that could do that. Music did it too, in many different ways, in many different forms. In 1976, the Sex Pistols played the Lesser Free Trade Hall in the city. The gig was watched by members of the Buzzcocks, Joy Division, Tony Wilson, Morrissey and, of course, Mick Hucknall.

All of them went out and added to the vibrancy of the city and the city added to the vibrancy of the world. It is a city which has been reborn in the last twenty years, but which remains rooted in those shared memories, the shared values and abstract notions like solidarity which become more than an abstraction or a meme during tragedies like these.

Those values do what music and sport do: they bring people together when the desire of those who murder children is to drive them further apart. And when those are the alternatives, when that is the choice in front of us, there is only one way we can go.